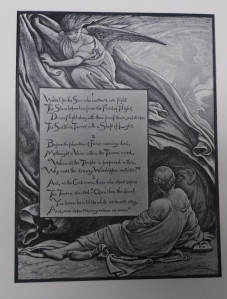

“Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! The Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light” (First edition: 1859)

These are the opening lines of one of the most enigmatic and celebrated poems in English literature, the translation from the original Persian of the verses of Omar Khayyám by the Victorian writer and scholar Edward FitzGerald. One of the best known poems in the world, it has been in continuous publication for well over a century and has been translated into more than 85 languages. Despite recent neglect in English literature studies, it remains arguably a significant poem and worthy of serious study. FitzGerald’s verse, imagery, and use of language have been a lasting influence on English literature, art and music. Dealing with the “Big Questions” of life: Why are we here? What’s it all about?, it remains perennially relevant and interesting. Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883), or “Fitz” to his friends, was a contemporary of Tennyson and Thackeray at Cambridge University and became a good friend of both. He was modest, scholarly and regarded as mildly, but pleasantly, eccentric. Coming from a well-to-do family, he was financially independent and without ambitions, and from early in life was able to devote himself entirely to scholarly pursuits; reading, travelling, visiting friends (although on first acquaintance he seemed shy he was in fact gregarious and had a gift for forming loyal and lasting friendships), and sailing. One of his closest friends was Edward Byles Cowell (1826-1903), a young scholar of Oriental languages, who encouraged Fitz to learn Spanish and Persian. In 1856 Cowell had discovered an uncatalogued manuscript in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, consisting of 158 four-line verses, (quatrains, or rubáiyát), now known as the Ouseley Manuscript. Cowell made a transcript of this for Fitz to translate, and later sent him more transcriptions from a manuscript in Calcutta reputed to be verses by the Persian astronomer-poet, Omar Khayyám (1048-1131). Apparently Fitz particularly welcomed having this new project to focus on since at the time he was recovering from a short and unhappy marriage. Many controversies surround the origin of the Persian verses FitzGerald translated, including the fundamental question of the identity of their author. Omar Khayyám was born in 1048 in the city of Nishápur (in modern-day Iran), where he also died in 1181, although he is believed to have travelled widely during his lifetime, both living and working in the cities of Samarkand, Bokhara, Merv and Isfahan. Although renowned for his great learning in mathematics and science and as a philosopher, contemporary records of his life do not mention that he was also a poet, the first reference to this appearing more than half a century after his death. Approximately 2213 rubáiyát have been attributed to Omar Khayyám, along with some philosophical essays and a work on algebra. The verses seem to express different philosophies and often conflicting opinions, and as a result, have given rise to considerable scholarly debate about whether they can really be attributed to the same writer and how they should be understood. Some scholars have therefore argued that Omar Khayyám the poet may not have been the same person as Omar Khayyám the famous astronomer, or indeed that the term “Omar Khayyám” may be the generic title of a genre of verse. However, the general consensus today is that the philosopher-astronomer and the creator of most of the rubáiyát are one and the same. In 1859, FitzGerald had a small edition of his first translations of a selection of the rubáiyát published anonymously. Of 240 copies, 200 of them remained still unsold after two years, and the bookseller Quaritch reduced the price from one shilling to one penny! Fortunately for posterity copies of this first edition were purchased by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) and George Algernon Swinburne (1837-1909), who both enthused about it and introduced it to their circle which created a demand for the poem. Four more editions were published in fairly quick succession, all anonymously, with varying numbers of rubáiyát and other textual changes, with the fifth and last edition of 1889, published 6 years after FitzGerald’s death, being the first with his name on the title page. Whether from fear of criticism or simply a natural shyness, Fitz never publicly admitted his authorship and sadly, he did not live to see the huge popularity of his Rubáiyát which had developed by the end of the century.

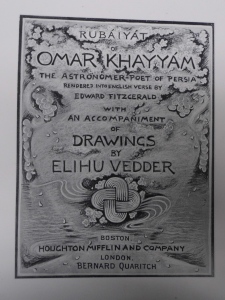

FitzGerald’s poem was also very popular in the United States, particularly following the publication by Houghton Mifflin, Boston, of the first illustrated edition in 1884. The illustrations were by Elihu Vedder (1836-1923), an American artist living in Rome, and an associated exhibition of the original drawings drew large crowds. Since then, the Rubáiyát enjoyed great popularity throughout the Victorian period and well into the twentieth century. During the Edwardian era in particular, it became a favourite choice for special Gift Book editions, and to a lesser extent this tradition continues today. Special Collections holds two particularly fine examples of this genre:

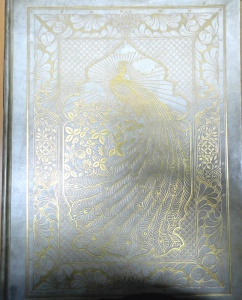

the finely bound copy at Sp Coll RF 405, published around 1910, was reproduced from a manuscript produced by Francis Sangorski (1875-1912) and George Sutcliffe and illustrated by E. Geddes. It has the text of the 1859 edition and includes an introduction written by Arthur C. Benson (1862-1925). It is number 546 of a limited edition of 550 copies printed on hand made paper and signed by F. Sangorski and G. Sutcliffe. This same company, specialists in hand bookbinding, were also commissioned in 1909 to produce “The Great Omar”, a fabulously ornate copy of the book with a binding studded with thousands of jewels. This took two and a half years to make and was offered for sale for £1000. However, as it found no immediate buyer it was auctioned at Sotheby’s, where it was purchased for £405 and sent to be shipped to America, unfortunately upon the R.M.S. Titanic, and so this sumptuous volume was lost forever.

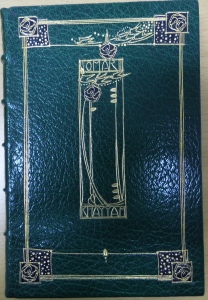

Another interesting edition published in 1902 (Sp Coll 735) features a beautiful binding designed by the renowned Scottish artist Jessie M. King (1875-1949).

From the outset, interpretations of the poem have been as diverse as its readership: Some have seen in it an encouragement to a life of hedonism and carousing, citing such lines as:

“Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend

Before we, too into the Dust descend,

Dust into Dust, and under Dust to lie,

Sans Wine, sans Song, Sans singer and – sans End!” (XXIII)

Others have seen it as a work of great beauty and profundity, with elements clearly influenced by mystical Sufism. Debate still continues over how much of FitzGerald’s poem is actually the work of Omar Khayyám and how much is in fact the work of FitzGerald himself. Certainly the text is demonstrably not a direct translation form the original Persian, but nor was it ever intended to be: FitzGerald himself described it as a “paraphrase”, and his aim was not so much to be a literal translation but to render the sense and spirit of a selection of the original Persian rubáiyát into good English verse. Arguably, the many unresolved questions and controversies surrounding it have not detracted from the poem but have in fact enhanced its appeal. As well as the intrinsic attractiveness of the verse, the enigmatic nature of its meaning as well as its origins have added to its mystery and created greater interest and a wide and diverse readership: copies of the book were carried and annotated by soldiers in both World Wars, and some lines have been quoted in famous speeches by Martin Luther King and President Bill Clinton. The phrase “The Moving Finger” from quatrain LI (first edition) has been used as the title of a novel by Agatha Christie. Indeed, the poem has become so much a part of the cultural heritage of the English speaking world, that some lines may be familiar even when their source is unknown. It seems reasonable to suppose that, as its great themes of the meaning of life, how best to live it, and of our mortality, are addressed anew by each generation, the poem will continue to be read, pondered and admired.

“The Moving Finger writes; and having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it” (LI)

The volumes described above are available for consultation in Special Collections, Level 12 of the University Library.

Sources used: Goldfarb, Sheldon: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition) article on Edward FitzGerald [page accessed on 21/5/2015]

Martin, William H. and Mason, Sandra: Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. A Famous Poem and its Influence. London, 2011 (Oriental PTO 703 2011-M)

Richardson, Joanna: Edward FitzGerald. London, 1960 (English MF93 RIC)

Hemmant, Lynette: Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Tadworth, 1979

Sangorski and Sutcliffe website article on “The Great Omar” [page accessesd on 1/6/2015]

Categories: Library, Reflections, Special Collections

Trollope’s Palliser Novels

Trollope’s Palliser Novels  Ghost Stories for Christmas

Ghost Stories for Christmas  Happy 150th Birthday to Alice!

Happy 150th Birthday to Alice!  Ancient art and ritual – letters of Jane Ellen Harrison

Ancient art and ritual – letters of Jane Ellen Harrison

So you do t even bother to put the poem in in it’s entirety?!

The full text is quite long, too long for our blog posts and can be found on other resources like Project Gutenberg https://www.gutenberg.org/files/246/246-h/246-h.htm

Am struggling to find a copy of a pocket sized edition of E.Fitzgerald’s translation of “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” & would be eternally grateful for any help with my quest .