Guest blog post by Roddy Simpson, photographer and writer on the history of photography. Roddy has researched and described a significant recent acquisition to our early photographic collections.

The Glasgow Photographic Association was active from 1862 until 1900 and succeeded the earlier Glasgow Photographic Society founded in 1854. A small carte de visite album, acquired by Archives and Special Collections in 2016, is a unique survivor of the Assocation. It includes images of the first office holders, who included some of the leading commercial photographers in Glasgow at the time, as well as prominent amateurs. The album contents also document the exploration of developments in technology during the first decades of photography, including what appears to be an early ‘selfie’ taken with the aid of magnesium and a mirror.

The album was given to the Association in the early 1860s, by the Treasurer at the time, Archibald Robertson. He was a leading commercial photographer who had premises in Glassford Street, Glasgow and in Dumbarton. He was a very active member and served, at different times, as Secretary, Vice President and President.

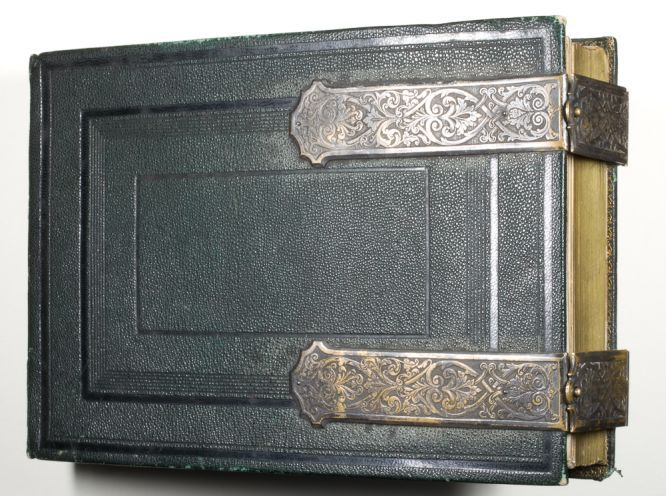

Reports of the Association’s meetings appeared in the photographic press and in particular The British Journal of Photography. At a meeting on 2 April 1863, ‘the Treasurer, Mr Robertson, had presented … an album, for which the members were requested to send in their cartes de visite’. The album would have looked impressive when new with its deep green, embossed covers and the detailed design on the pair of silver plated fastenings.

The Glasgow Photographic Association album (Dougan Add. 141)

Robertson’s original intention appears to have been to collect photographs of all the members of the Association. (This was during the craze for cartes de visite, known as ‘Cartomania’. Cartes de visite had been introduced in France in the mid-1850s. They were the size of a visiting card (hence the name), with a small photograph attached. This was the first time that images of ordinary people became widely accessible and relatively affordable and they flocked to photographers’ studios. Cartes de visite were usually purchased in quantities of a dozen for a few shillings and were given to family and friends. Albums were produced to hold and display them.) The Association’s album only contains identifiable photographs of the early Committee members and seems to have evolved a broader remit, to include cartes de visite related to the Association’s activities.

The album contains 39 cartes de visite, mostly portraits, and two larger sized cabinet portraits with two cabinet ‘view scraps’ of scenes in India pasted into the front of the album. The album begins with members of the first committee. Unfortunately, some of these photographs have gone missing in the 150 years since the album was compiled, but the original captions remain on the page.

The committee was a mixture of commercial and amateur photographers. John Kibble (1815-1894) was an inventor and engineer as well as an amateur photographer. In 1858 he created the world’s biggest camera, which was mounted on a horse-drawn cart. The Kibble Palace in Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens began life as a large conservatory erected at Kibble’s home. (See Kibble’s entry in The Glasgow Story.) The business of Andrew MacTear (1817-96) included lithography and engraving as well as photography; his fellow Vice President, Alexander Macnab (born c1822) was a commercial photographer. The Treasurer, Archibald Robertson (1830-1901) was a commercial photographer but the Secretary, Edmund Brace (c1828-1881), was a prominent wine and spirits broker. Of the Council members, James Ewing (1832-1866) and John Stuart (1831-1907) were commercial photographers and the family business of John Spence Jr (1835-1890) was described in the Glagow Post Office Directory as ‘optician, mathematical instrument maker and photographic apparatus maker. Also supplied chemicals and other necessaries for the photographer’. Further information about Archibald Robb has not been discovered; he was possibly an amateur photographer. John Jex Long (c1825-1893) and Duncan Brown (1819-1897) were amateurs, although a surviving collection of Brown’s work (in Glasgow School of Art Archives) is evidence of his talent, documenting aspects of Glasgow life from the 1850s until the 1890s.

There is only one identified photograph of a later Committee member: James Bowman (1822-95), a commercial photographer who joined the Committee in November 1863 as a member of Council. There were no women members of the Association, despite a suggestion by Archibald Robertson to follow the example of the Edinburgh Photographic Society. However, open or ‘popular’ meetings were regularly organised which many women attended.

Meeting of the Glasgow Photographic Association, 19 February 1863 (Dougan Add. 141 Item 46)

Some idea of these meetings is given by one of the most exceptional images in the album. It is an interior photograph, taken by artificial light, showing a gathering of the Association including an exhibition of photographs. There are some technical inadequacies to the image, which is a little blurred but it is still remarkable and captures the bustling atmosphere of the event. It was reported in the British Journal of Photography as ‘A Soirée, Exhibition and Conversazione’ organised on 19 February 1863 ‘at the Merchants’ Hall, Glasgow, which was completely filled’. Among the photographs on display were ‘statues of the Vatican’ by Robert Macpherson (1814-72) which can be seen in the photograph of the event. The evening ended with a magic lantern display and ‘first amongst the slides were transparencies of the pictures taken at an earlier part of the evening by the electric light, and which had since been printed from the negatives’. The photographer involved is not named but it could have been James Bowman as his name appears on the print in the album.

Carbon printing was a process often discussed by the Association. It was a more permanent method of producing prints because it was pigment rather than silver based and not susceptible to fading. The advantages were recognised but there were concerns about the costs and complications of the process. There were rival processes, although that patented by Joseph Swan became the most widely used. The British Journal of Photography reported that, at the meeting on 6 October 1864, ‘the specimen of Pouncy’s process submitted by Mr Gilfillan was generally admitted to be exceedingly satisfactory; Mr James Ewing, however, remarking that Swan’s pictures were the finest he had seen produced by the carbon process’. The ‘Pouncy specimen’ is included in the album (Item 16) but is not the only carbon print. On 12 December 1878 ‘Mr Paton, of Greenock, was asked to practically demonstrate the carbon process and…went through all the manipulations. At the close of the demonstrations…members remarked upon the beauty and simplicity of the process’. An example is included in the album and is an excellent photograph both technically and artistically. The circumstances of how it was produced are written on the back and initialled by Archibald Robertson.

James Paton (born c 1830) had his studio at the Esplanade, Greenock but the identity of the subject in the photograph is not known. Her style of dress is distinctive and the jewellery she wears may show an interest in the Celtic Revival movement. She is holding a rolled up sheet of music, which may indicate a personal interest, but the content has not been identified.

Advances in photographic equipment also fascinated the members of the Association. This is shown in the album by a series of ‘Pistolgraph’ photographs. These are likely to be the result of a meeting on 2 November 1865 when it was reported that: ‘Mr Robert Dalglish Jun exhibited one of Skaife’s Pistolgraphs and explained its working and construction…the first one which had been shown [and] several plates were developed through the medium of magnesium light’.

The Pistolgraph was introduced in 1859 by Thomas Skaife (1806-76), a London photographer who was obsessed with instantaneous photography. The Pistolgraph was a small metal camera producing negatives about one inch in diameter (3 x 3 cm) on glass plates and had a lens with a wide aperture which made exposures of a fraction of a second possible. Although more of a novelty than practical commercial use, it aroused considerable interest. Two of the photographs in the album appear to be by Robert Dalglish and one of these (Item 36) could have been developed at an Association meeting. The description ‘developed’ is not clear but the implication is that it means exposed and developed. The Pistolgraph used wet collodion plates which had to be prepared just before exposure and developed immediately afterwards when the plates were still moist.

The photograph captioned as a Pistolgraph in the album and attributed to R Dalglish Jr is an interior view of a fireplace with a mantle-piece and mirror above. The use of magnesium as an artificial source of light for this interior view was innovative but not especially rare by this time. The objects on the mantle-piece do not quite obscure the figure of a man with dark hair and what could be a small camera, which can just about be made out in the mirror. So, the concept of ‘selfies’ is not new!

There are other Pistolgraph photographs in the album. These are identified as being by James Skaife and several are commercially produced images. One of these shows the potential of the Pistolgraph for ‘snapshot’ and candid photography. It was taken on an express train at full speed without the subject’s prior knowledge.The photograph is a silhouette and, though lacking in detail, is recognisable. It demonstrates aspects of photography which would be fully realised in the future with advances in equipment and materials.

The use of artificial light to produce photographs was a topic which the Association explored on numerous occasions. As a large proportion of members were commercial photographers there was also a business interest here. Photography was generally undertaken by natural daylight, in studios with large areas of glass to maximise the light available, but daylight was not always in ready supply, especially in the short days of winter. A reliable source of artificial light would increase the time available for taking photographs.

At an Association meeting in January 1879 members attended a demonstration of the Luxograph at the studio of Turnbull and Sons at 75 Jamaica Street, Glasgow. The Luxograph was a lantern which burned chemicals to produce a brilliant light. It was reported that: ‘Mr Finlayson was the first sitter and … two cameras were set and a carte and cabinet negative taken at the same exposure … The President [John Jex Long] then sat for his portrait’. At the following meeting on 13 February 1879 ‘Mr Turnbull submitted prints from the negatives that were taken at the previous meeting by the Luxograph. The pictures were much admired, some members expressing themselves as convinced that better could not be produced by good daylight’.

All the Turnbull photographs in the album are almost certainly examples of the use of the Luxograph and those from the demonstration have the date written on the back ‘Taken 23rd January 1879’ and initialled ‘A.R.’ for Archibald Robertson. They are also ink stamped ‘This portrait was taken (without daylight) by the “Patent Luxograph Aparatus”’. There is a carte de visite and cabinet print of the same man, ‘Mr Finlayson’. Alexander Finlayson (1847-1917) was a commercial photographer with a studio at 180 West Princes Street, Glasgow and he would have been around thirty years old when the photographs were taken.

The other carte de visite (Item 30) is of ‘The President’, John Jex Long who also appears in the album as a member of the original Committee (Item 11). The exposure time could be indicated on another Turnbull carte de visite (Item 29) which has ‘2 seconds’ written in pencil on the back. The ‘Mr Turnbull’ mentioned is almost certainly Robert Turnbull, the son of Charles Turnbull (died 1874) who had set up the studio. His younger brother, also called Charles, was also a photographer at the studio.

Artificial light was again the topic on 5 February 1880 when John Urie Jr (born 1854) of Dundee ‘exhibited his apparatus for taking pictures by gaslight and…various members brought cameras and dry plates and over a dozen exposures were made, with varying results’. At the meeting in March ‘pictures produced by gaslight were shown by Mr Urie, some from the negatives taken at a previous meeting’.

The Urie photographs in the album are almost certainly related to this gaslight demonstration; although none are dated, some state that they are by gaslight. It is not possible to identify those taken at the meeting but Item 25 is a possibility as it is not an obvious studio setting. It is unlikely that the inclusion of this photograph is arbitrary and, unlike the other Urie cartes de visite, it has the Glasgow address rather the Dundee address listed first. The Glasgow address was the studio of John Urie senior (1818-1910) who would have been over sixty at this time; it may be him in the photograph. He had succeeded John Jex Long as President of the Association and Long, as President, had been photographed in the previous Luxograph demonstration.

It can also be speculated that John Urie junior is the person in two other cartes de visite (Items 33 and 41). He would then have been in his mid-twenties. As his photographs by gaslight are likely to have been experiments initially, it is likely that the subjects are family and friends rather than commercial clients.. The studio in Dundee run by John Urie Jr does not appear to have operated for long. He was back in Glasgow with his parents for the 1881 census and there was no entry in the Dundee Directory after this date.

Photograph taken by gaslight by John Urie (Dougan Add. 141 Item 32)

After the gaslight photographs there is no other content in the album that can be linked to any specific reports in the photographic press. At its meeting in October 1881 it was proposed ‘that the Association should procure a scrap book in which to keep any prints that might be presented’. This was agreed, it being ‘remarked that there were already sufficient to fill a large album’. Cartes de visite were still produced but they were not as popular and larger prints were more in demand.

The Glasgow Photographic Association continued in existence until 1900 when it was reported: ‘The Glasgow Photographic Association has fallen on evil days. For three or four years past it membership, while suffering from the inroads made by death and resignation, has not recruited by as many as half a score all told. The monthly meetings for several winters have been attended by a handful, and altogether it seemed as if the Association would shortly cease to be through sheer decay. Rather than court this fate, the office bearers and the faithful few who answered the summons to a recent general meeting resolved to suspend the Association meetings by a twelvemonth’ . The suspension proved permanent and, by this time, various other photographic societies were operating in Glasgow.

Sources:

The British Journal of Photography, 1862-1900

Glasgow Post Office Directory, 1862-1863

Torrance, D Richard, Scottish Studio Photographers to 1914 and Workers in the Scottish Photographic Industry, (The Scottish Record Society, Edinburgh: 2011)

See also:

Full catalogue descriptions for the album and its contents (Dougan Add. 141)

Blog post about the album by Megan Hon, student placement project

Glasgow Photographic Association Papers in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow (ref: MS 250)

Categories: Archives and Special Collections

![Dougan Add_141_25 Photograph [of John Urie senior?] possibly taken at Association meeting (Dougan Add. 141 Item 25)](https://universityofglasgowlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/dougan-add_141_25.jpg?w=516&resize=516%2C810&h=810#038;h=810)

![Dougan Add_141_25 Verso Reverse of photograph [of John Urie senior?] (Dougan Add. 141 Item 25)](https://universityofglasgowlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/dougan-add_141_25-verso.jpg?w=508&resize=508%2C810&h=810#038;h=810)

Are you dancing?: The Scottish Ballet Archive

Are you dancing?: The Scottish Ballet Archive  Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’

Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’  Lou and Kitty: a friendship in letters

Lou and Kitty: a friendship in letters  Preserving History: Challenges of Storing Old Beer Bottles and Cans in Archives and Special Collections Storage

Preserving History: Challenges of Storing Old Beer Bottles and Cans in Archives and Special Collections Storage

I was very very pleased to come across this photograph album on the University of Glasgow Library site as it includes a photograph of my great great grandfather Edmund Brace. I did not have any other picture of him, and I am writing a book about my family history, and he is an important character in it! The dates given for him are incorrect by the way – his dates were 1827-1915.