We’ve recently blogged about how examining physical marks in surviving old books can give us clues about whether they have been read or not. In this guest blog, Allie Newman, a current postgraduate student in Information, Management and Preservation, discusses a few other things physical marks can tell us about the producers and users of old books.

When undertaking research in a library special collections, you never know what you might find. Catalogues of the collection tend to give a good overview of what lurks in the pages of their books, but sometimes, you stumble upon things that are truly surprising. Recently while doing some research on an English bookbinder, I came across a rather grisly scene of book production gone wrong:

No, this is not the scene of an attempted book murder! This is a case of hand finishing (in this instance, rubrication of initials) gone wrong, but the bibliographic jury is still out on how exactly the red paint came to be in streaks down the front and back of a gathering. Was it hung up to dry, and the paint ran down the page? Was it laid out on something when paint was spilled on it, causing the paint to run along the edges of what was supporting it? Whatever the cause, it is a particularly obvious example of the kind of traces left by scribes, printers, and readers in manuscripts and early printed books. Such marks are supremely useful to researchers, as they serve as physical evidence of how people constructed and interacted with books throughout their histories.

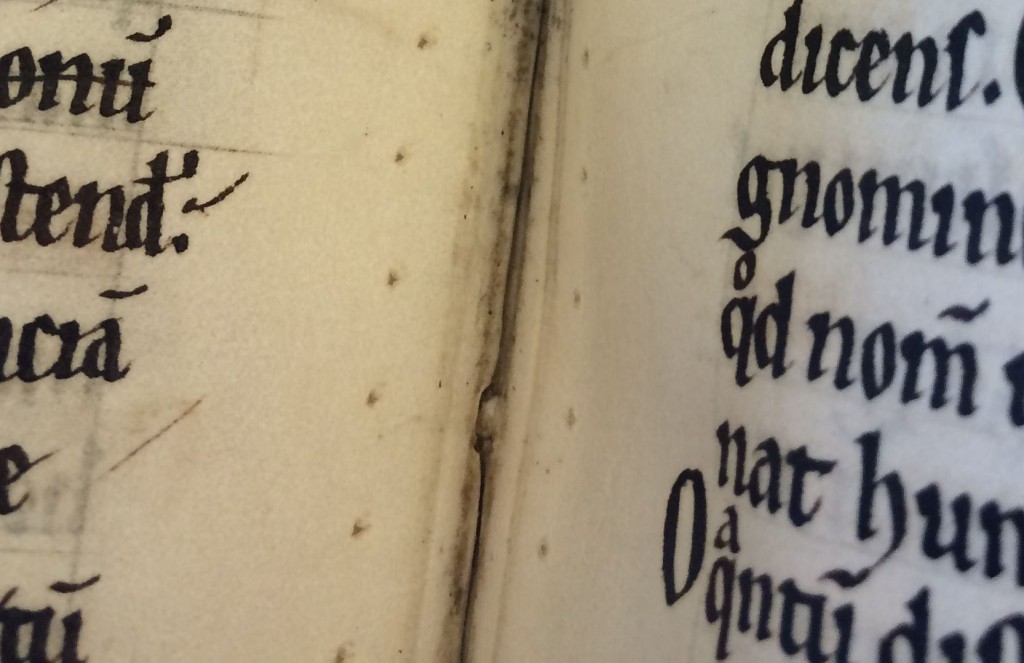

Some traces aren’t as evident as the above rubrication disaster; take, for example, these minuscule holes found in the gutter of a medieval manuscript.

- Raban Maurus’ “De Universo” 12th Cent. (MS Hunter 366 (V.1.3))

Rather than coming from a particularly regimented family of bookworms, the origin of these holes is human in nature- known as pricking holes, they are evidence of the scribal process of ruling before writing the text. The scribe would evenly prick a row of holes down each side of the page and draw straight lines between them, producing a sort of medieval notebook page. On the left side of the page in the image above, you can see some of these ruling lines beneath the text and, sure enough, they line up perfectly with the holes.

After the scribe finished writing the book’s text, it was still subject to marking and corrections by its new owners. These marks take a variety of forms, including crossing out text, making notes above the text, and flagging important passages they wished to come back to later.

This symbol, found in the margins of text, is actually a complex monogram of the Latin word nota, meaning “take note”. The nota mark could be extended to mark out long passages of text – here, it’s marking out the beginning passage of the Book of Job.

For more exact locations, the pointing hand drawing known as a manicule, from the Latin manicula (meaning “little hand”) was an option. These little hands varied in complexity based on the artistic skill (or boredom) of the note-maker — the above manicula is rather simplistic, but there are examples featuring elaborate sleeves, and even ones decked out in armoured gloves!

But not all drawings in books serve a purpose.

This pot-bellied jester figure was either drawn by a creative scribe or a bored reader. The text he is featured in is the same one that contains the above manicule, although he was drawn in a different ink. The work that both he and the manicule come from is a very no-nonsense tract on the duty of the clergy to their congregation—hardly a place for a jester, but such doodles are relatively common in both manuscripts and printed books. Sometimes they originate from ambitious pen trials (where a reader or scribe is testing the fidelity of their newly cut quill or new pen nib), but often there is no deeper meaning behind their existence other than the desire to doodle. It’s amazing to think that, just as students draw in their notes and textbooks today, some poor late medieval medical student or scribe was disenchanted enough with their work to create amusing art!

Of course, the marks that perhaps bring us closest to the makers and readers of manuscripts and early printed books are fingerprints.

This thumbprint comes from the same book as the rubrication disaster in the first example—clearly, we are dealing with some messy printers! Seeing the impression of a Renaissance printer’s or reader’s thumb really drives home the idea that there is a direct connection between we, the modern readers and researchers, and individuals from nearly 600 years ago. But beyond the sense that people are reaching out to us from history, such prints give us interesting glimpses of the printing process and how pages were handled. Sometimes, if prints like this are found in manuscripts, it can indicate that that particular manuscript was used as an exemplar when a print version was being made.

Beyond the content of their text, manuscripts and early printed books have numerous stories to tell. Some jump right out at you, but others you have to look for. Reading a book as an object, rather than focusing solely on its content, opens up new avenues of understanding and research that produce a more well-rounded perception of the human environment in which it was made, read, and is preserved today.

Categories: Special Collections

Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’

Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’  The Arte of Faire Writing

The Arte of Faire Writing  Visualizing Collation in the Hunterian Manuscript Collection

Visualizing Collation in the Hunterian Manuscript Collection  Sugar Machines: How Archives in Glasgow hold pieces of Caribbean History

Sugar Machines: How Archives in Glasgow hold pieces of Caribbean History

Reblogged this on 7artesliberales.