A guest blog post by Charlie Catterall, from the Memorialising Scottish Literature & Culture placement, working on the Papers of Joan Ure (ASC 011 A: Writings) in Archives and Special Collections

For five weeks at the beginning of 2024 I underwent a student placement at the University of Glasgow’s Archives and Special Collections department. This placement introduced me to Joan Ure, a poet, playwright, and author, that is so criminally underrated that it’s unlikely I would have ever come across her works without this placement. A writer who, from the five weeks of reading through her writings scattered with personal edits and annotations, has become a new literary friend of mine.

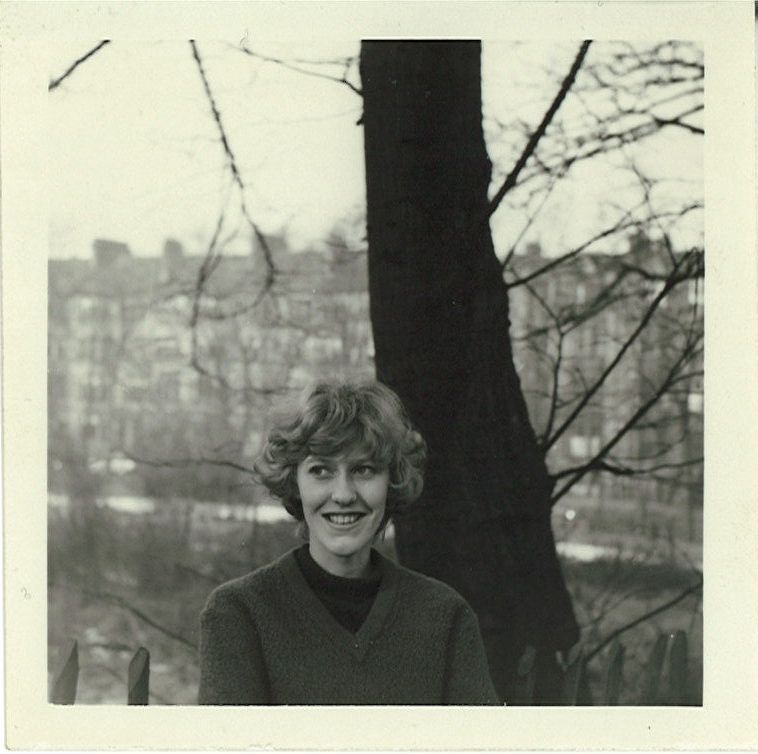

To fully discuss Ure’s work, a brief look at her biography is helpful. Joan Ure was born Elizabeth Clark in Newcastle upon Tyne to Scottish parents in 1918 but lived the majority of her life in Glasgow, moving here in her early childhood and staying until her death in 1978. This Scottish upbringing but English place of birth creates an attitude towards identity that is a key topic in Ure’s work, expressing both a love and infuriation for a Scottish selfhood and, further, depicting her own displaced nationality, never being able to fully adopt a Scottish identity due to her English birthplace.

Despite excelling in school, her education is cut tragically short, as she is forced to leave at fourteen to adopt a parental housewife role following the death of her mother. In 1939 Ure marries a Glaswegian businessman, and gives birth to her daughter the same year, quickly assuming the same domestic role, whilst beginning to write and quietly pursue a literary career. This conflict of identities plagues all her writings, her voice inherently interested in the contradictory selfhoods of the academic creator and the domestic wife. The adoption of a pseudonym projects this conflicted identity, allowing her to physically separate her roles as wife and writer with a different name and identity for each.

Ure is primarily known, though still very limitedly, for her work as a playwright, but it’s her poetry that speaks to me most. When working through and logging Ure’s literary works during my placement, it was her poems that often stopped me in my tracks, enforcing moments of reflection as I consumed the beauty, and vulnerability of her work, moved by her ability to articulate such complex truths of the female experience. The logging of Ure’s documents produced a unique relationship to the poet, her handwriting sprawling annotated edits and notes across the typescripts. The personal nature of this created a feeling like reading someone’s diary, making me feel close to the creation and creator of the poetry I was consuming. This illusion of personal closeness creates a literary relationship that could only be curated from viewing the archived drafts of these poems, but one I aim to project.

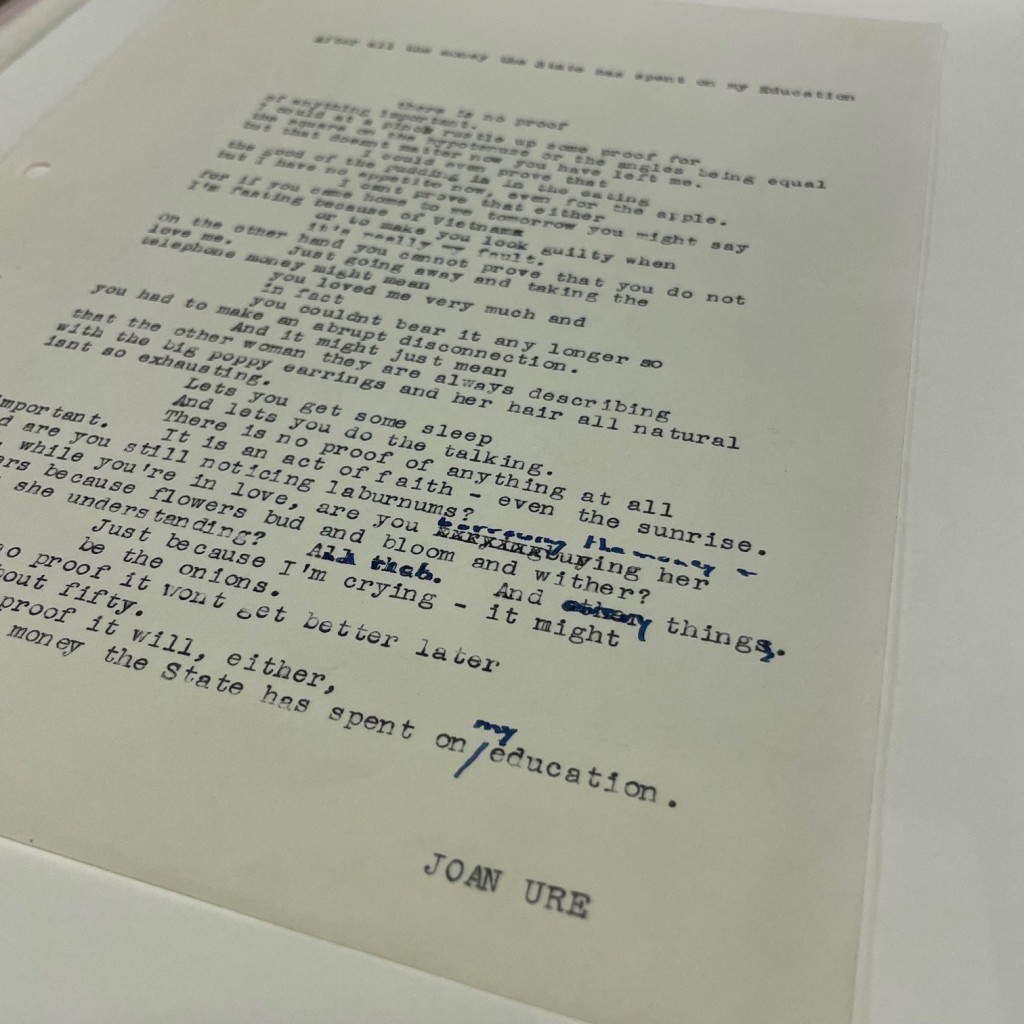

‘After all the money the states spent on my education’ was the first of her poetry I came across. It is a piece that really spoke to me, as a final year student the title initially grabbing my attention, and its content quickly following suit. In this piece Ure’s poetic voice is so vulnerably true to the female experience, especially as an academic. The poem depicts the protagonist being left for another woman, and the lies she tells herself to make this more tolerable. But the poems’ overriding comment is despite all the education she has; it doesn’t change how she can be made to feel hurt by someone else or fix the situation she is in. Ure depicts the paradoxes of the academic vs domestic spheres for women and how, traditionally, we often feel we must choose only one, as it seems the characteristic these spaces enforce us to adopt cannot cross. Thus, her education makes her feel she should be above giving into such hurt, she should be smarter than being deceived or giving into the stereotype of the ‘heartbroken’ emotional female, but her natural confinement to relationship structures inevitably means giving into the feminine stereotypes of weakness and subordination that these relationships, especially in Ure’s early twentieth century context, so often contain.

Here Ure writes in a poetic voice that’s very much ahead of its time, its tone conversational, tongue-in cheek and vulnerably feminine, as well as the manipulation of spacings, creating a poetic voice very similar to Liz Lochhead’s that comes twenty or so years later. The date of Ure’s writing is hard to specify in these works, due to their nature as unpublished private documents, but it’s assumed to be in between 1940 and 1975. It’s hard to understand why her work is so underrated when Lochhead’s feminine vulnerability is marked as revolutionary a few years later, while the patriarchy is almost certainly to blame its time her work is revalued for the excellence it is, its voice and subject fitting neatly with the infamous female Scottish poets of the 80s, a cannon in which Ure’s poetic work belongs.

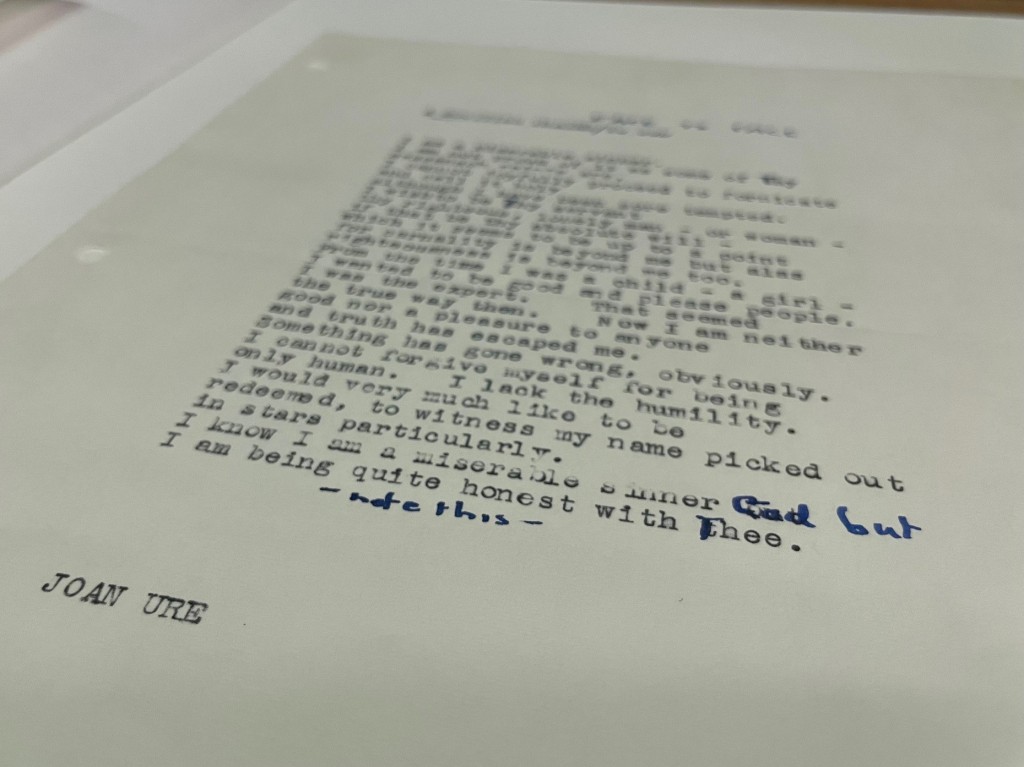

When cataloguing Ure’s work another piece that struck me was ‘A Scottish Prayer’, the archives containing serval versions of the poem with different titles and edits written across the typescripts. This creates the illusion of a real connection to the piece and Ure, visually seeing her editing processes and the transitions the poem went through between versions. But a further personal assumption can be made, as it’s easy to get the gist of Ure as a very self-critical and particular woman, picking apart each stanza and scrawling the word ‘bad’ over lines, like seen in the picture on the left, the final lines of the poem edited simply with ‘hate this’. These harsh notes are inked over original lines I could still read and enjoyed, I often wished I could reach out and tell her how effective I thought they were.

The poems content fits neatly within this perception of Ure; It is completely self-scathing, repeatedly referring to herself as a ‘miserable sinner’. The poem makes several references to both female and Scottish identity politics, both wrapped up in religion. Ure had a strict presbyterian upbringing, effecting the way she viewed femininity and female roles, clearly shown in this poem. This is highlighted most evidentially by lines; ‘I wish to be thy servant, thy righteous lonely man’ projecting a religious will, with the ‘righteous man’, but also referencing the stereotypical ‘servant’ role of wife. Further, in a national context, this alludes to Scotland’s perceived ‘servant’ relationship to England.

But the poems lines that spoke to me the most are; ‘I would very much like to be redeemed, to witness my name picked out in stars particularly.’ It is a beautifully written line that carries such a sad message about self-worth, that transfers to the female experience, Scottish identity, as well as Ures own personal life. The need to be redeemed, to never feel good enough, or the want to be ‘special’, is a type of self-criticism that transfers to the feminine experience and its desire to always portray an image of perfection. In a Scottish context, this references the ‘greatness’ Scots believe the country has, but being inherently subordinated by England stunts this ‘greatness’, thus, outlining a desire to be redeemed as the country we feel we are or could be. And finally, it references Ures owns literary career, suggesting that in another life, she could succeed simply as an academic, not debilitated by gendered issues, and picked by fate as one of the greats, like she truly deserves to be.

The introduction to Joan Ure is one I will not forget, completely unique to my university and literary experience so far, the personal nature of thumbing through Ure’s documents creating a closeness to the poet and her works I have never previously experienced. A closeness that is heightened by the relatability of the poems contents, so eloquently echoing truths of the female experience, and I hope one day, with the work of the Archives and Special collections department, she can be a friend to everyone.

Categories: Archives and Special Collections, Library

Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘Why Have I Never Heard of Joan Ure?’

Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘Why Have I Never Heard of Joan Ure?’  Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘When looking to the future, bitterness co-exists with optimism…’

Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘When looking to the future, bitterness co-exists with optimism…’  Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘This moment of humanity, found amongst the unvarying typescript, was a real treasure’

Joan Ure: MSLC 2024 – ‘This moment of humanity, found amongst the unvarying typescript, was a real treasure’  Through conservation keyhole: William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin and His Legacy in Conservation

Through conservation keyhole: William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin and His Legacy in Conservation

Leave a comment